Since President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, his administration has acted on a number of fronts to reverse Trump-era restrictions on immigration to the United States. The steps include plans to boost refugee admissions, preserving deportation relief for unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and not enforcing the “public charge” rule that denies green cards to immigrants who might use public benefits like Medicaid.

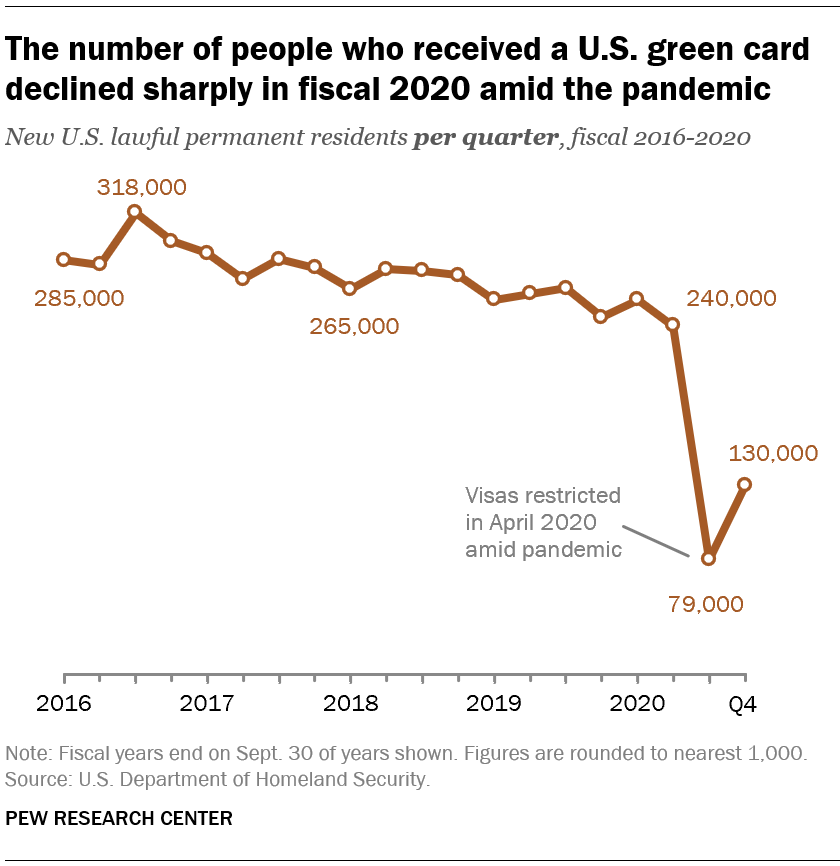

Biden has also lifted restrictions established early in the coronavirus pandemic that drastically reduced the number of visas issued to immigrants. The number of people who received a green card declined from about 240,000 in the second quarter of the 2020 fiscal year (January to March) to about 79,000 in the third quarter (April to June). By comparison, in the third quarter of fiscal 2019, nearly 266,000 people received a green card.

Biden’s biggest immigration proposal to date would allow more new immigrants into the U.S. while giving millions of unauthorized immigrants who are already in the country a pathway to legal status. The expansive legislation would create an eight-year path to citizenship for the nation’s estimated 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants, update the existing family-based immigration system, revise employment-based visa rules and increase the number of diversity visas. By contrast, President Donald Trump’s administration sought to restrict legal immigration in a variety of ways, including through legislation that would have overhauled the nation’s legal immigration system by sharply reducing family-based immigration.

How we did thisThe Biden administration has proposed legislation that would create new ways for immigrants to legally enter the United States. The bill would also create a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants living in the country.

To better understand the existing U.S. immigration system, we analyzed the most recent data available on federal immigration programs. This includes admission categories for green card recipients and the types of temporary employment visas available to immigrant workers. We also examined temporary permissions granted to some immigrants to live and work in the country through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status programs.

This analysis relies on data from various sources within the U.S. government, including the Department of Homeland Security, Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Department of State, Federal Register announcements and public statements from the White House.

The Senate is considering several immigration provisions in a spending bill, the Build Back Better Act, that the House passed in November 2021. While passage of the bill is uncertain – as is the inclusion of immigration reforms in the bill’s final version – the legislation would make about 7 million unauthorized immigrants eligible to apply for protection from deportation, work permits and driver’s licenses.

Amid a record number of migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border, Biden reinstated in December 2021 a Trump-era policy that requires those who arrive at the U.S.-Mexico border and seek asylum to wait in Mexico while their claims are processed. Biden had earlier ended the Migration Protection Protocols, or “Remain in Mexico” policy, and then restarted it after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lawsuit by Texas and Missouri that challenged the program’s closure. Asylum seekers do not receive a legal status that allows them to live and work in the U.S. until the claim is approved.

Overall, more than 35 million lawful immigrants live in the U.S.; most are American citizens. Many live and work in the country after being granted lawful permanent residence, while others receive temporary visas available to students and workers. In addition, roughly 1 million unauthorized immigrants have temporary permission to live and work in the U.S. through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status programs.

Here are key details about existing U.S. immigration programs, as well as Biden’s proposed changes to them:

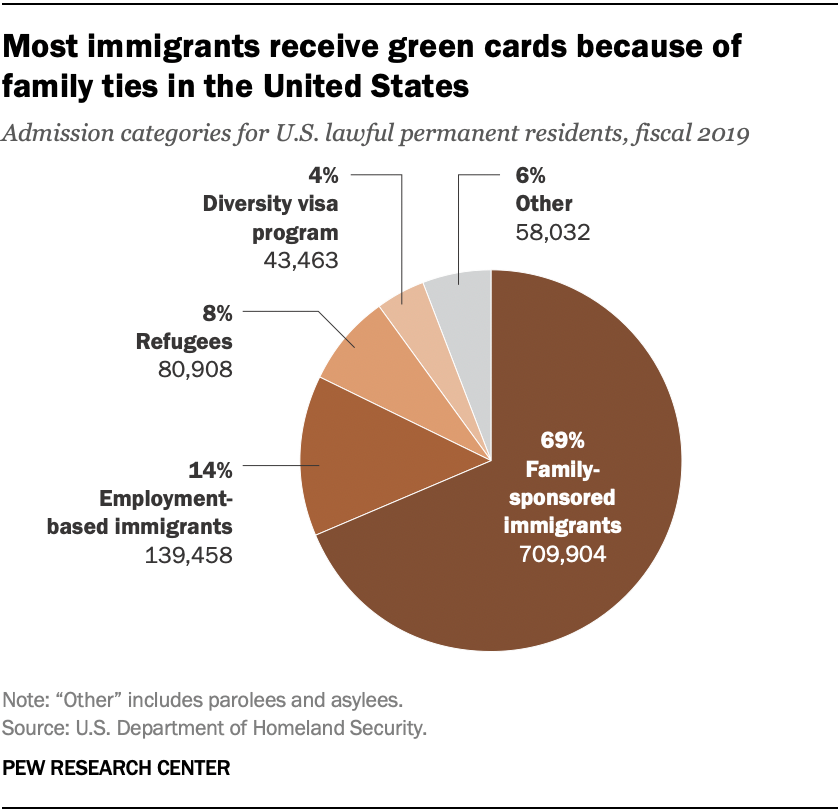

In fiscal 2019, nearly 710,000 people received lawful permanent residence in the U.S. through family sponsorship. The program allows someone to receive a green card if they already have a spouse, child, sibling or parent living in the country with U.S. citizenship or, in some cases, a green card. Immigrants from countries with large numbers of applicants often wait for years to receive a green card because a single country can account for no more than 7% of all green cards issued annually.

Biden’s proposal would expand access to family-based green cards in a variety of ways, such as by increasing per-country caps and clearing application backlogs. Today, family-based immigration – referred to by some as “chain migration” – is the most common way people gain green cards, in recent years accounting for about two-thirds of the more than 1 million people who receive green cards annually.

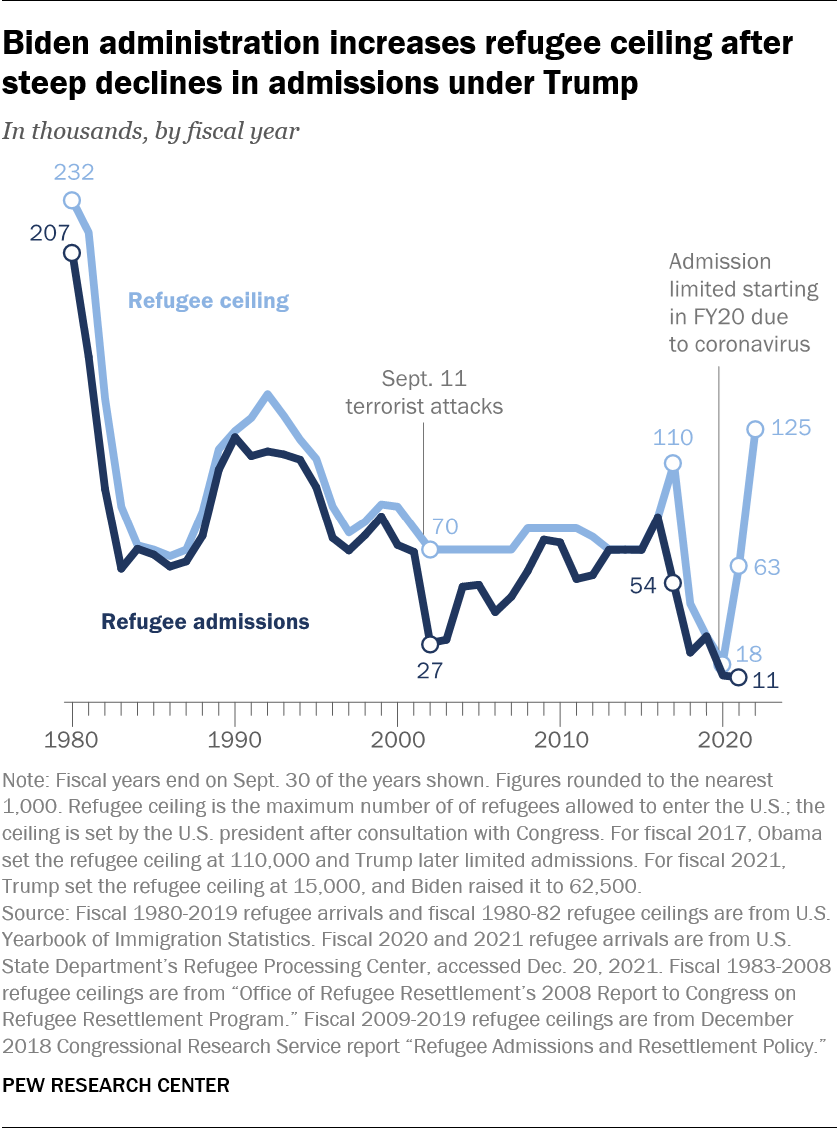

The U.S. admitted only 11,411 refugees in fiscal year 2021, the lowest number since Congress passed the 1980 Refugee Act for those fleeing persecution in their home countries. The low number of admissions came even after the Biden administration raised the maximum number of refugees the nation could admit to 62,500 in fiscal 2021. Biden has increased the refugee cap to 125,000 for fiscal 2022, which started on Oct. 1, 2021.

The low number of admissions in recent years is due in part to the ongoing pandemic. The U.S. admitted only about 12,000 refugees in fiscal 2020 after the country suspended admissions during the coronavirus outbreak. This was down from nearly 54,000 in fiscal 2017 and far below the nearly 85,000 refugees admitted in fiscal 2016, the last full fiscal year of the Obama administration.

The recent decline in refugee admissions also reflects policy decisions made by the Trump administration before the pandemic. Trump capped refugee admissions in fiscal 2020 at 18,000, the lowest total since Congress created the modern refugee program in 1980.

In fiscal 2019, the U.S. government awarded more than 139,000 employment-based green cards to foreign workers and their families. The Biden administration’s proposed legislation could boost the number of employment-based green cards, which are capped at about 140,000 per year. The proposal would allow the use of unused visa slots from previous years and allow spouses and children of employment-based visa holders to receive green cards without counting them against the annual cap. These measures could help clear the large backlog of applicants. The proposed legislation also would eliminate the per-country cap that prevents immigrants from any single country to account for more than 7% of green cards issued each year.

Each year, about 50,000 people receive green cards through the U.S. diversity visa program, also known as the visa lottery. Since the program began in 1995, more than 1 million immigrants have received green cards through the lottery, which seeks to diversify the U.S. immigrant population by granting visas to underrepresented nations. Citizens of countries with the most legal immigrant arrivals in recent years – such as Mexico, Canada, China and India – are not eligible to apply.

The Biden administration has proposed legislation to increase the annual total to 80,000 diversity visas. Trump had sought to eliminate the program.

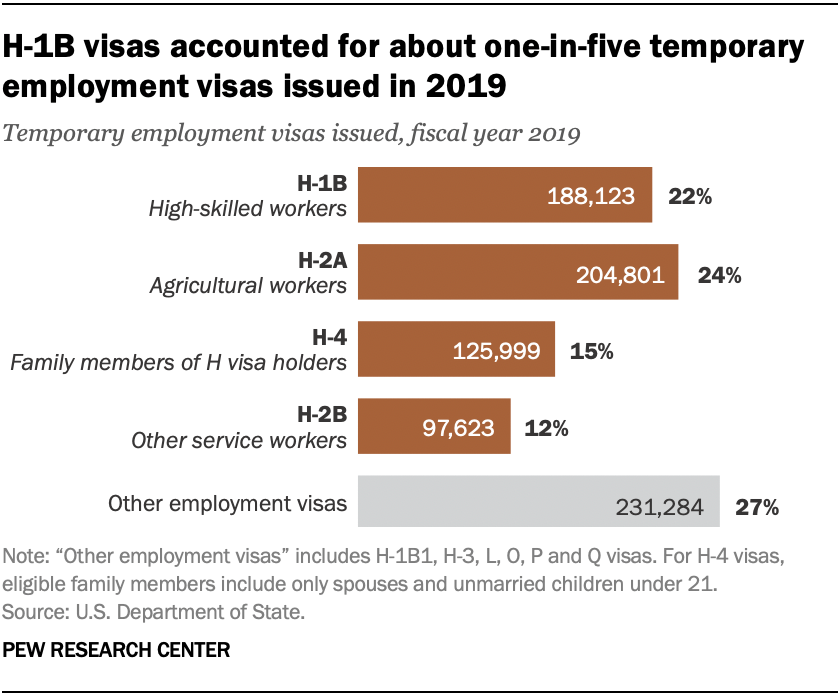

In fiscal 2019, more than 188,000 high-skilled foreign workers received H-1B visas. H-1B visas accounted for 22% of all temporary visas for employment issued in 2019. This trailed only the H-2A visa for agricultural workers, which accounted for nearly a quarter (24%) of temporary visas. In all, nearly 2 million H-1B visas were issued from fiscal years 2007 to 2019.

The Biden administration is expected to review policies that led to increased denial rates of H-1B visa applications under the Trump administration. In addition, Biden has delayed implementing a rule put in place by Trump that sought to prioritize the H-1B visa selection process based on wages, which would have raised the wages of H-1B recipients overall. Biden also proposed legislation to provide permanent work permits to spouses of H-1B visa holders. By contrast, the Trump administration had sought to restrict these permits. The Trump administration also created an electronic registration system that led to a record number of applicants for fiscal 2021.

A relatively small number of unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. under unusual circumstances have received temporary legal permission to stay in the country. One key distinction for this group of immigrants is that, despite having received permission to live in the U.S., most don’t have a path to gain lawful permanent residence. The following two programs are examples of this:

About 636,000 unauthorized immigrants had temporary work permits and protection from deportation through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, as of Dec. 31, 2020. One of Biden’s first actions as president was to direct the federal government to take steps to preserve the program, which Trump had tried to end before the Supreme Court allowed it to remain in place. DACA recipients, sometimes called “Dreamers,” would be among the undocumented immigrants to have a path to U.S. citizenship under Biden’s immigration bill. Senators have also proposed separate legislation that would do the same.

Overall, it is estimated that more than 700,000 immigrants from 12 countries currently have or are eligible for a reprieve from deportation under Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, a federal program that gives time-limited permission for some immigrants from certain countries to work and live in the U.S. The program covers those who fled designated nations because of war, hurricanes, earthquakes or other extraordinary conditions that could make it dangerous for them to live there.

The estimated total number of immigrants is based on those currently registered, in addition to those estimated to be eligible from Myanmar – also called Burma – and Venezuela.

Immigrants from Venezuela and Myanmar are newly eligible for TPS under changes made after Biden took office in January 2021 by the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees the program. The government must periodically renew TPS benefits or they will expire. The department extended benefits into 2022 and beyond for eligible immigrants from nine nations: El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. In addition, the Biden administration expanded eligibility for immigrants from Haiti based on recent turmoil.

Biden and congressional Democrats have proposed granting citizenship to certain immigrants who receive TPS benefits. Under Biden’s large immigration bill, TPS recipients who meet certain conditions could apply immediately for green cards that let them become lawful permanent residents. The proposal would allow TPS holders who meet certain conditions to apply for citizenship three years after receiving a green card, which is two years earlier than usual for green-card holders. By contrast, the Trump administration had sought to end TPS for nearly all beneficiaries, but was blocked from doing so by a series of lawsuits.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published March 22, 2021.